The minimum wage history in Australia.

Like many countries, Australia has a national minimum wage. It’s the lowest pay rate a person can receive for the work they’re doing (not including people who are on apprentice and trainee rates, junior pay rates or employees with disability rates).

Australia’s minimum wage is set by the Fair Work Commission, the independent umpire for workplace matters, and is reviewed in June each year. Currently (as of 1st July 2023), the National Minimum Wage is $23.23 per hour or $882.80 per week.

Unfortunately, our system is broken. Too many Australians on the minimum wage don’t get enough money to make ends meet. You shouldn’t be working full-time and not have enough money to live, right?

How did we get to this point? To understand minimum wages better, we’ve written a two-part blog to explain it. In this first article, we look at the history of this system in Australia. In our second article, we explain what we should have instead.

Australian minimum wage history – it all started after Federation

Australia adopted a minimum wage in 1907 and at the time it was considered pretty ground-breaking. When the minimum wage was set up, the President of the Conciliation and Arbitration Court (a precursor to the Fair Work Commission), Henry Bourne Higgins, in his famous “Harvester Judgement”, said the wages had to be ‘fair and reasonable‘ for a family of five to live on.

To determine what that was, he interviewed not only male workers but also their wives. This was the first time a living wage was determined on a person’s needs, not what the company wanted to pay.

According to former Assistant Secretary of the Australian Council of Trade Unions, Tim Lyons, it showed what the purpose of the minimum wage was.

“(Any person) who is working may not be well off, but they will not be in poverty,” he said.

The system worked by ranking all jobs against each other.

“People will think it’s nuts now, but for some decades, the entire wages system for most people revolved around the rate of pay for a man who has a metal industry trade,” Tim explained.

The independent umpire would base each pay around a percentage of a metalworker’s salary.

“If a metal tradesman gets 100% of the basic wage, a cleaner gets x percent of the base wage and an electrician gets y,” he said.

It was a pretty frugal wage, but it rose over time and for a while, Australians on the minimum wage and all the different industry awards were receiving a relatively decent standard of pay.

Our minimum wage was a big step forward, but it was far from perfect. In 1912 women were paid just 54% of men and indigenous Australians were also paid less.

Unions have fought over many years to remove pay discrimination. In 1972, it was ruled that women and men who did the same work should be paid the same. The last race-based pay rates were removed in 1966.

However the battle for equal pay continues – in 2023, for every dollar men earn, women earn 77 cents, which adds up to $25,596 per year.

What happened next?

However, in the early 1990s, there was a big shake up.

The federal Labor government, with ACTU support, changed how the system worked so its focus moved to enterprise bargaining.

“Instead of having a system that was based on what a quarterly tribunal decided, it was based on what you could get out of your own boss,” Tim explained.

For some people, it worked well, such as those who were working on the wharves.

“They’re at a choke point in the economy where their labour costs are very little, but the capital costs of what they do is very high,” he explained.

But for most industries where you need many people to get the job done, it’s not as effective.

“If you need a lot of people to do it, like the service sector, then those kinds of systems have been pretty problematic,” Tim explained.

These changes happened at the same time as the massive growth in the service sector economy. Many new service sector workers were women and very few had access to enterprise bargaining, partly due to low levels of union membership.

All of this meant that the nexus between the strong and the weak in the labour market was broken. Some workers (mostly men) began to gain through enterprise bargaining, while others (mostly women) were stuck in a minimum wage system that was falling behind. As a result, the gap between average and minimum wages grew wider and wider.

Instead of the minimum wage being a foundation of pay, it became a safety net. This was a really fundamental change.

How do we know it’s not working?

National President of the United Workers Union, Jo Schofield, explained that ever since the 90s, workers on minimum wages have seen their wages fall further and further behind.

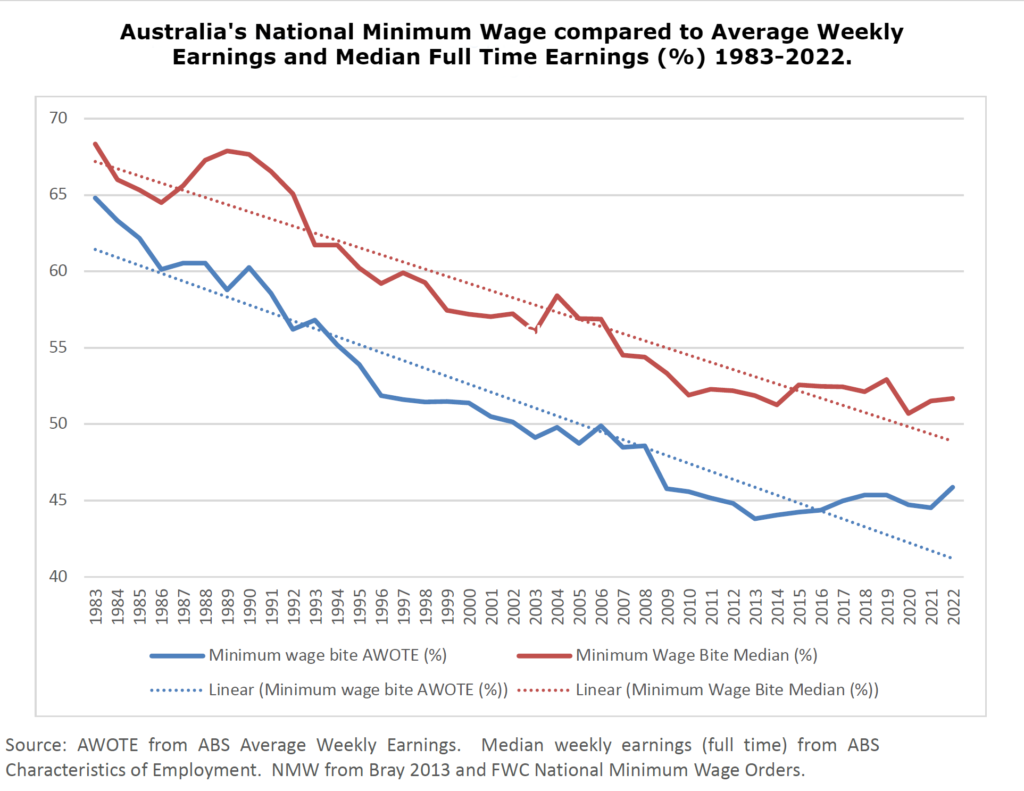

“The standard way low pay is understood, is that if you’re paid 60% or less than someone on a middle income, then you’re low paid. Until the late 1990s, our minimum wage stayed above this key threshold. But since then, Australia has been on a downward slide,” she said.

As you can see from this graph, it’s fallen really quickly.

“What that shows is that if you’re on the minimum wage, you’ve seen your living standards fall further and further behind the rest of the community. Unions have fought incredibly hard over the years to keep pushing wages up and we’ve had some wins, but the truth is the current system has a fundamental flaw – for decades we allowed our minimum wage to become something that is simply not enough to live on. That should never be allowed to happen.”

“While bigger increases in the minimum wage over the past few years have helped, they have been quickly eaten up by even bigger rises in the cost of living,” Jo explained.

We know from our members what an impact this is having. Lots of you are priced out of rental markets in capital cities. You’ve told us about how you’re struggling to pay for medical expenses, heating bills and even basics like groceries.

“If you work full-time, you shouldn’t make an international definition of low paid,” Tim said.

And if you’re thinking, ‘but I’m not on a minimum wage, this has nothing to do with me,’ then think again. The minimum wage underpins all our award wages which affect close to 3 million people. Awards are set by industry and there are over 100 awards, with industries ranging from aged care to hospitality to cleaning.

If we can increase the minimum wage, that helps everyone else push for better pay.

What would work better?

Stay tuned for our next blog where we outline a plan for a better minimum wage.

But suffice to say: (warning: another spoiler) if we can improve the minimum wage system, we can build a better system for all workers.

Interested in learning more? Join UWU now to get expert advice and support from your union.